1) Carvel; 2) Omission; 3) Regret; 4) Ricky; 5) Second Walk; 6) Every Person; 7) -00Ghost27; 8) Wednesday's Song; 9) This Cold; 10) Failure33 Object; 11) Song to Sing When I'm Lonely; 12) Time Goes Back; 13) In Relief; 14) Water; 15) Cut-Out; 16) Chances; 17) 23 Go in to End; 18) The Slaughter

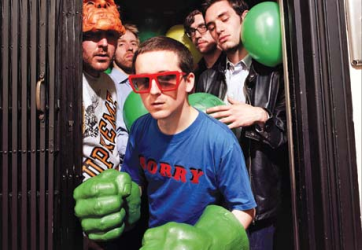

What Frusciante sounds like when he sets out to make his own big-budget recording. Don't worry about this being stifled by overproduction though; if anything, this is a prime example of how to use the studio space correctly and create your masterpiece.

Key tracks: "

Carvel", "

Omission", "

Time Goes Back"

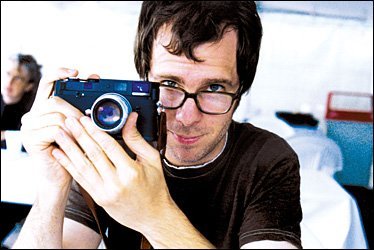

A persistent characteristic throughout

John Frusciante's solo recordings is how modest they are. In contrast to his time with the

Chili Peppers and the extensively labored, expensively produced album sessions spent at top-of-the-line studios, Frusciante's own albums have mostly been recorded at home and with only a few additional names in the credits lists.

Shadows Collide with People is, to date, the first out of only two exceptions, and it's the major one. It's a big budget, hi-fi experience meticulously recorded in a professional studio; a self-admitted response to anyone who called Frusciante's prior recordings unfinished or messy, going all the way to prove he could do the opposite if he wanted to.

Shadows Collide with People introduces its densely constructed sound right off the bat. Every note played and every sound made has been treated with pristine perfection, there's layers upon layers of vocal melodies and guitars that would make it impossible to accurately replicate it live, and the majority of the tracks are amplified by prominent keyboard and synthesizer parts. Considering the timing, it's easy to see

Shadows Collide with People as Frusciante's personal counterpart of his then-band's

By the Way, released a few years prior and in itself a melody-rich and studio-heavy album that was heavily weighted towards Frusciante's contributions, featuring many of the same musical cues that

Shadows is full of. Familiar Peppers names even feature here, with Chad Smith powerhousing the drums on each song and Flea making a surprisingly understated appearance in "The Slaughter", and with frequent brother-in-arms and future Peppers guitarist Josh Klinghoffer having an audible backing role across the tracklist. But where

By the Way was rather blunt dynamically, Frusciante himself helms the producer's seat on

Shadows and ensures that the sound world isn't an overproduced and overstuffed mess, and rather each element is given its own space. It's a rich and warm sound, both when filling the room out loud and when intimately observed via headphones.

Shadows Collide with People sounds

gorgeous, and a great deal of effort has been put forward to make it so without sacrificing anything.

The production values of

Shadows are especially noteworthy not just because of the sound itself and its contrast against the rest of Frusciante's discography, but the (possibly coincidental) effect they have had on Frusciante's songwriting as a whole. With the clear sound, the ability to layer multiple elements precisely and the piece-by-piece recording process, Frusciante approaches the songs with the mindset of having all that utility in hand and makes use of it in the song arrangements in a practically liberating way. The songs were written with these possibilities in mind and designed to use all those elements to their advantage, building upon their already-strong core melodies with frequent multi-tracked backing vocals, several guitar parts trading spaces and keyboard textures that are like punctuation or font changes for the thoughts and emotions the songs wish to raise. It's that interesting, and in this case often beautiful, point where the songwriting and the production hold hands so well that they both support one another, and reach to the listener all the more strongly because of their collaboration.

That freedom of possibility brings out two things. One,

Shadows is Frusciante's most openly joyous album. Many of its songs could be called downright anthems, Frusciante bellows out the abstract but appropriately scene-setting lyrics with complete conviction and major chords are everywhere. Frusciante's physical and mental rehabilitation post-coming clean is a big part of the man's mythology, but that newfound appreciation for life is the most apparent here, still relatively recent after the recovery: it leads to the passion evident in the performance and the lyrics frequently referencing learning from life's mistakes. This then leads to a kind of positive boundlessness for the album, expressed through Frusciante indulging himself with big choruses, dramatic musical explosions, grand swoons and other notions that might be a bit too 'obvious' and bombastic for your average Frusciante home recording - which, while not experimental most of the time, have their own sense of song structures and lack of reliance for any of the above.

But here you have "Carvel" opening the album with a proper bang after its bubbly intro and sounding colossal from the get-go, only becoming more towering as it goes on and Frusciante keeps dialing up its rock anthem intensity. It's all giant guitar walls, fist-pumping sing-alongs and sort-of-choruses, and it's while unusual to hear Frusciante play something so bold and powerfully direct under his own name, it's near-empowering to hear it: "Carvel" is a phenomenal song that constantly one-ups itself with another section more awesome than the prior one. Meanwhile "Song to Sing When I'm Lonely" and "Wednesday's Song" are two of Frusciante's most straightforward pop songs, and they're both disarming in their sheer melodic wonder - they're the sound of summers and life at its most colourful, brought through a warm sound and rich tune. While the tricks they employ aren't new to Frusciante, the unashamed openness of them has been rarer in his back catalogue.

Behind the production and the structural choices, the songs of Shadows Collide with People are consistently strong. Each of the actual songs offers something new, has the power to stay with you long after the album has finished and strongly resonates even within the greater context of Frusciante's whole discography. That's staggering on its own, but even the interludes (the ones with all the number titles, representing various milestone ages for Frusciante) all feel absolutely crucial to the album's flow - in fact, the hauntingly atmospheric ambient cut "23 Go in to End" is one of the album's big stand-outs, a veil of dreamy sound covering the world in a particularly poignant way. Out the "proper" songs, many - "Carvel", "Wednesday's Song", the achingly lovely Klinghoffer duet "Omission" and the bittersweet beauty of "Ricky" - are among the best within Frusciante's discography. Even "Regret", built entirely on two repeated lines and a couple of similarly recurring melodies, is an impressive example of how the same passage can be wholly different when the production behind them changes and grows, from downbeaten to defiant; it's the underdog that unexpectedly reaches the goal far more impressively than you'd expect. And while much of Shadows' strength comes from its more delicate moments, it can also be physically powerful when it wants. Smith's drumming, here in its peak strength, injects the songs with a thunderous energy which especially makes the more guitar-heavy rock-out moments even wilder, whether contributing to the majesty of "Carvel" or powering through the brief but punchy "Second Walk", which is downright breath-taking in its sheer speed and in-your-face melodies (particularly when Frusciante bring out the sparkling guitar part towards the end).

But the light that shines the brightest is "Time Goes Back". It's a marvellously effortless and staggeringly beautiful song that doesn't brag with complex arrangements or intricate structures, but Frusciante's delivery is phenomenal and makes the song sound so effortlessly majestic. It's where many of Shadows' traits all come together to reach the peak: it's blissfully lovely and larger-than-life in its power, melodically rich and thoroughly resonating. Other songs on the album may arguably be more ambitious or more upfront, but "Time Goes Back" hits a special nerve simply by how its delivered. It could just well my favourite moment Frusciante has committed on tape; or so it at least feels every time it reaches its heights and feels like a revelatory moment for the power of music.

That notion is where that top rating comes from. Over the course of this review it may have become apparent that Shadows Collide with People often whelms me, repeatedly and throughout over the course of is duration, and in a way that feels like the first time, every time. As a John Frusciante album it's the strange one. It bears little similarity with anything else the man has released under his own name, both in songwriting and especially the sound. But it simultaneously showcases the best sides of Frusciante in the clearest way: his vocals, his detailed arrangements, his style of guitar playing, and how Frusciante brings those elements out on this record is sublime, often perfect. It's not that the big production makes Shadows stronger than his other albums, it's that the production has taken Frusciante down to a path where he can really show off those ideas. He immerses into the songwriting so well that you can hear the love and devotion he has for his craft that he's famously obsessed about. When an artist puts so much of themselves into something, the excitement becomes a tangible part of what comes out from the speakers and resonates through the listener. It's a series of moments that take one aback with the impact of a gut punch; and once the album has finished, there's that curious, almost physical feeling of the world feeling a little different after going through all that splendour. It's the embarrassingly subjective hallmark of an all-time favourite album.

Take that particular super-subjectivity away and you're still left with an incredible landmark album for Frusciante. It doesn't overshadow the rest of Frusciante's works and I don't hold their more home-knit nature against them in comparison, but if you want the best possible idea as to why Frusciante is a noteworthy artist on his own right, this holds all the tricks.

Rating: 10/10