Disc One: Hotel: 1) Hotel Intro; 2) Raining Again; 3) Beautiful; 4) Lift Me Up; 5) Where You End; 6) Temptation; 7) Spiders; 8) Dream About Me; 9) Very; 10) I Like It; 11) Love Should; 12) Slipping Away; 13) Forever; 14) Homeward Angel; 15) 35 Minutes [hidden track]

Disc Two: Hotel Ambient: 1) Swear; 2) Snowball; 3) Blue Paper; 4) Homeward Angel (Long); 5) Chord Sounds; 6) Not Sensitive; 7) Lilly; 8) The Come Down; 9) Overland; 10) Live Forever; 11) Aerial

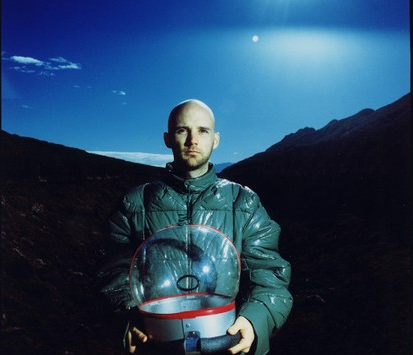

Moby as a rock star. The tunes are there but it's not a perfectly comfortable fit.

Key tracks: "Raining Again", "Dream About Me", "Slipping Away". Hotel Ambient: "Swear"

Moby, always the honest nice guy, has openly admitted that he spent most of the 00s cruising around on auto-pilot, trying to write popular music that he felt was expected of him rather than what he was personally inspired to write. He had become a global superstar and was treated as such and he struggled to cope with it. His last album 18 had struck a few huge international hits with “We Are All Made of Stars” and “Extreme Ways”, which were effectively rock songs played through an electronic filter and where Moby took a proper front role in his music. Thus, when two rock songs became some of the biggest hits of his career, he didn’t want to disappoint his million-head audience and saw this as people wanting more of the same. He grabbed his guitar and started writing big rock hits, taking on a true frontman role for the first time when facing the big audience. Technically he had already done this once before with Animal Rights but this time people actually wanted to hear the songs.

Which brings us to our main point of contention: Moby is not a rock star. He’s a great musician, a fantastic producer and an all-around lovely guy but not a rock star. He’s a good performer but his voice isn’t cut out for stadium-sized rock songs and his lyrics can’t take being so exposed. He mumbles rather than soars, his vocal range is fairly limited and he’s the kind of writer who’s willing to earnestly use “thou” just to get a rhyme in (“Lift Me Up”). Furthermore, his preferred style of production is fantastic for the line of music he normally associates himself with, but the clean, polished sound takes the edge off any attempt at a rock song. Moby mentions in the liner notes how he doesn’t want to make sterile music, which is downright ironic considering how cleanly-shaven and dirt-free Hotel is. Listen to the drum and piano intro to “Raining Again”: what tries to be an energetic build-up comes across flat, like a basic pre-set rhythm loop on a set of cheap keyboards. The music in Hotel is something that wants to be played loud but lacks the balls for it, written by someone whose forte lies in instrumentals and which is performed by a man who’s far more comfortable behind his synthesizers than he is in front of the microphone.

It’s also still good music, even though it really doesn’t make a lick of sense considering all I’ve said. For the duration of the entire album you’re repeatedly reminded of the myriad of issues stemming from the points raised above, and yet nearly every track manages to survive through it. With most it’s a simple case of the actual songs being good to listen to. Rock-Moby isn’t a particularly intricate or complex songwriter and Hotel is largely made out of very basic verse/chorus/verse structures (with a big emphasis on the chorus part), but that worked well for him with “Extreme Ways” and “We Are All Made of Stars” and it works well for him here. It helps the songs overcome their weaknesses: “Raining Again” blows away its limp intro into a faint memory as it turns into a joyous stadium-stomper and despite its lyrical shortcomings “Lift Me Up” is an exciting roof-raiser that acts like a rock-rearranged dance track. Now and then Hotel also uses its building blocks exquisitely and everything falls into place the right way. The clean and shiny production compliments the sunny and happy feeling of “Dream About Me” perfectly and really emphasises its utter loveliness, while “Slipping Away” utilises Moby’s weary voice for a perfect bittersweet punch when combined with the song’s melancholy melodies.

The ambient theme, as a matter of a fact, is just as notable as the rock material during the Hotel era. The special edition of the album came with the bonus disc Hotel Ambient, which got almost as much promo time on the album’s website as the main disc itself. It’s a selection of 10 original ambient tracks as well as an extended version of the already wonderful “Homeward Angel” and as far as bonus discs go, it’s borderline essential; especially if you enjoy Moby’s ambient works. The production that didn’t quite fit the main album is much more suited towards the minimalist electronic compositions, coming off as glacial and crystalline rather than sterile. As expected of an ambient album it’s not a particularly hook-driven collection, but each song feels as distinguishable as anything on the more obviously different main album. “Swear” and “Blue Paper” in particular are actual delights, as well as the extended version of “Homeward Angel” obviously. What makes the songs stand out from a lot of other ambient, including the majority of Moby’s own material, is that the atmosphere it produces is bright and perky for most parts, rather than the usual dreaminess. It’s the kind of ambient album you’d play during the day rather than at night.

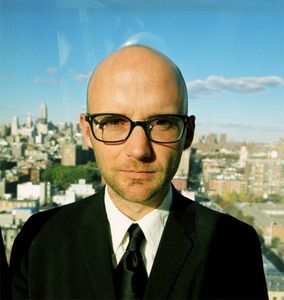

One of the reasons I sometimes find numerical ratings really awkward are cases like Hotel. To me Hotel Ambient – which at the end of the day is a bonus disc – is such an essential part of Hotel that I find it hard to separate the two: together they’re the full Hotel experience and that brings a whole load of nerdy rating-related issues, especially when very few are going to get access to the extras (although Hotel Ambient has since been re-released separately on digital platforms). The main Hotel itself is hard to rate as it is, anyway. It’s a strange album where I can hear every single flaw and which I find easier to criticise than praise, yet when it comes down to it I’m more than happy to play it from start to finish and enjoy the ride. Part of it is probably honest nostalgia: Hotel’s release ties down to the period of time where I had started to become a heavy internet user and artists had begun to take advantage of the online world. One of my biggest memories surrounding Hotel relates to the pre-album hype around it on Moby’s own website, which hosted a Flash animated mini hotel to explore and where you could find samples of the upcoming songs from. I spent ages there in awe of fancy modern gimmicks and repeating the samples, and I still associate the album with all that. The other part is that there’s a really good album within Hotel, but the inspirational wires got mixed somewhere and the musical ideas appeared in the head of the wrong artist. It’s a strange case of the artist sounding more comfortable with the bonus material than the main album itself and the whole thing has been puzzling me ever since the album was released. Hotel is the height of Moby’s post-Play wilderness years and while it has a way of getting you into it, it never stops being a slightly awkward dress-up performance.